Herbert Yaka:

Racehorse Photographer’s Photo Finishes Determined Champions

By Elise Takahama

It’s been decades, but whenever JoAnn Jamora smells cigars, memories of bustling racetracks wash over her. She grew up watching horses race, and remembers wandering around the tracks, picking up discarded tickets to check if they turned out to be winners.

Meanwhile, her father sat in a tiny photo booth above the racetrack, in his element.

At the time, Herbert Yaka was working as a photo-finish photographer at racetracks in Southern California — and his job was to capture the moment the racehorses crossed the finish line, helping judges determine the ultimate winner.

While sometimes more than $1 million was wagered a night and Yaka wasn’t immune to feeling the pressure, he said the job was usually a “piece of cake.”

He compared his cameras, which were shutterless ones used for “slit photography,” to a picket fence: If you remove one of the pickets, there’s a gap in the fence, he said. When photographing races, that gap is the finish line, with the horses running behind the fence. As the horses approach the finish line and near the gap — or slit — Yaka would flip two switches and start to move the film in his cameras, capturing the horses at the same speed at which they were traveling.

He would always use two cameras, just in case one malfunctioned, he said.

The moment the last horse crossed the finish line — he was required to photograph every horse, not just the winners — Yaka would pull the large, wooden window of the photo booth shut, turning his office into a darkroom within seconds.

Once he pulled the window closed, he was in a race of his own.

“You’re trying to do it as fast as you can,” he said. “Even one minute is a long time to wait.”

He would tear the film out of the camera — working quickly but expertly — develop the film in a cocktail of preheated chemical solutions, dunk it in a water bath, then project an image of the last few seconds of the race up to a panel of judges, who ultimately made the final call of which horse took first, second and third place.

“When I used to do it, I had to wear a smock because all these chemicals are flying around in the dark.”

The whole process usually took about 20 seconds, he said.

In nearly 30 years of photographing horses, he never missed a finish.

“I still have nightmares about that, I still do,” he said.

But it was still his dream job, he said.

August 24, 1945: Yaka family - Back row: Sumiko (Sue), Tomiko, Leslie, Miyoko, Sachiko (Violet), Roy (14 yrs old) Front row: Herbert (10 yrs old) , Sojo, Makato, Patrick

Circa 1956 - Roy Yaka, Roderick Abe, Herb Yaka

Yaka grew up as one of eight kids in a sugar plantation town called Hanamā’ulu in Kauai. His father was the town barber, while his mother worked odd jobs — from hospital laundry rooms to pineapple canneries. Both were raised in Nago, a city in Okinawa. His father immigrated to Hawaii in 1913 when he was 21 and brought Yaka’s mother to the United States about seven years later, Jamora said.

When Yaka’s eldest sister married the son of a dairy farmer, he and his older brother, Roy, often visited her and worked on the farm.

“It was the beginning of the Korean War, so they needed help because a lot of the young men were taken away,” he said. He was 13 at the time.

When he became a sophomore in high school, he moved in with his sister on the farm, milking cows while his brother made deliveries.

Yaka’s schedule was consistent: Wake up at 4:30 a.m. and start milking at 5 a.m. Finish up by 7:30 a.m., shower, then head off to school. He was back at the farm by 1:30 p.m. — often leaving school early to start the afternoon round of milking.

“I worked long hours, but I was getting paid like a grown man,” he said.

Roy Yaka

It was around this time that his brother, who was four years older, became fascinated with cowboys, Yaka said. The two would chase cows around the farm, trying to rope them, until one day Yaka’s brother bought a couple horses to practice with.

“My brother loved it so much that when he graduated high school, he asked our parents if he could go to the Big Island and work as a paniolo (Hawaiian cowboy) at Parker Ranch, which was the biggest ranch in Hawaii,” Yaka said.

“Roy was small in stature, but strong and a hard worker,” Yaka said. “I miss him a lot. He was my idol. He could do anything. He was, like, 4’10” — a little old guy.”

When Yaka turned 19, he enlisted in the U.S. Army and spent two years in Korea, though fortunately, he said, most of the action had already ended by the time he arrived. After the Korean War ended, he briefly returned to Hawaii, before he and his brother decided to move to California. Yaka studied electronics and eventually started working for former defense contractor Litton Industries, while his brother became a jockey.

Late 1954/Early 1955 - He left Korea in Dec 1955

Roy Yaka has since died, though his fascination with horses and passion for racing was the starting point for his younger brother’s career.

Yaka’s racetrack work began after he had started showing up around the tracks to watch his brother race, he said. Over time, he got to know trainers and businessmen in the racing community, and eventually started filming races and selling tickets for the tracks.

In 1971, he was hired by a photo-finish business called Photo Chart. He hadn’t worked in a darkroom before, but Yaka was a fast learner.

“I just loved to watch the horses race,” he said.

Photo Chart, which worked with local racetracks, sent Yaka to tracks all over Southern California, but he spent most of his time at the Los Alamitos racetrack, he said. Sometimes, his wife Eva and daughter would bring a picnic basket and visit him, Jamora said.

June 18.1990 - Roy Yaka Owner & Trainer

In 1981, Yaka started his own business called Acculine Photo, and shot finishes at the Los Alamitos and Pomona tracks. When Los Alamitos introduced night-racing, he would finish a job at Pomona during the day, then rush over to Los Alamitos and tackle the night shift.

“When you’re young and crazy, nothing bothers you,” Yaka said. “Now when I think back, I’m like, ‘Oh my gosh, I did all that?’”

Jamora said she thinks her father’s busy schedule is one of the reasons she’s such a night owl now.

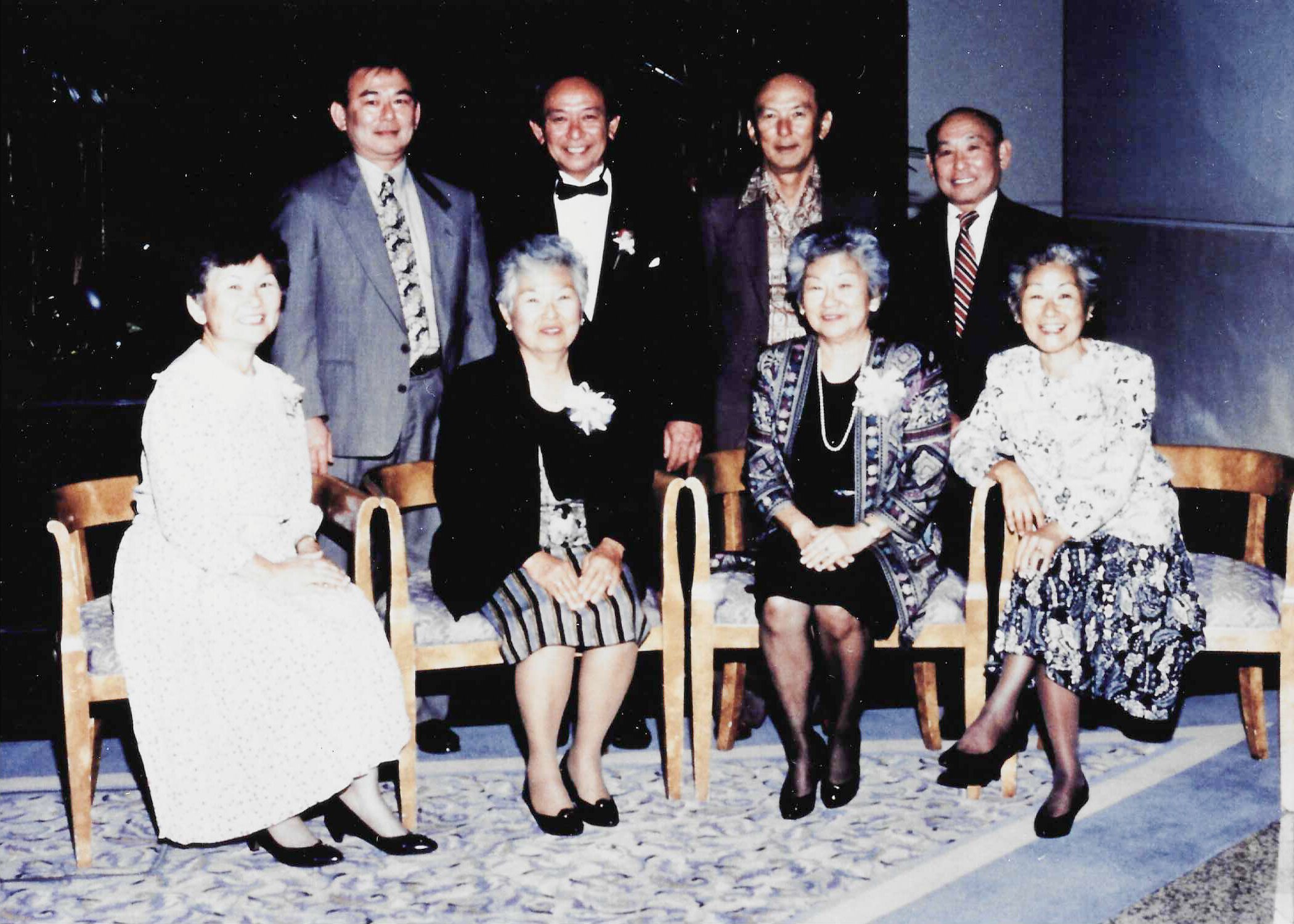

March 19, 1994 - All eight siblings at JoAnn’s wedding. This was the last time all 8 siblings were all together. Back, Left to right: Patrick, Herbert, Leslie, Roy Front, Left to right: Sumiko (Sue), Tomiko, Sachiko (Violet), Miyoko

“I would be in my room and I could hear his Volkswagen puttering around the corner,” she said. “I would stay up so I could make sure he got home.”

Orlando Gutierrez started working with Yaka at the Los Alamitos racetrack in 1993, when he was a 20-year-old student studying communications at California State University, Fullerton.

“He was already a staple here at the racetrack,” Gutierrez remembered. “He had been doing photo finishing for many, many years.”

Gutierrez, who still works at the racetrack as its marketing director, said he remembered Yaka as a warm person and a “great gentleman,” who showed him how the photo-finishing process worked in the racetrack’s darkroom.

“It was a lot of fun to watch an artist do what he does,” he said. “I have nothing but fun memories.”

Yaka started gradually retiring in 2000 when he was 65, around the time Japanese companies started developing new photo-finish equipment that didn’t require a darkroom, he said.

June 17, 2019 - Eva and Herb at Miyajima Island

“My equipment was too antique, because Kodak was going to discontinue making the special film we used,” Yaka said. “So I had to buy Japanese equipment.”

He sold his business, Acculine Photo, to a Japanese company, but stayed on their payroll for five years as a consultant before officially retiring.

Since then, Yaka has spent his time golfing, traveling and enjoying life with his family.

Herbert and JoAnn