Joe Aihara: Empathy and Excellence in the Classroom and on the Court

By aimee kim

The influence of Japanese language teacher Joe Aihara reaches far beyond the classroom, extending to hands-on, immersive experiences of cultural exchange and even to the basketball court. Born in Princeton, New Jersey and raised in Orange County, California, Joe has taught Japanese and coached basketball, primarily in the Anaheim Union High School District, for thirty years.

My parents Setsu and Haruo

The Japanese language has been a major, if not always the most welcome, presence in Joe’s life since his childhood.

“My late father, Haruo, was born in Numazu, Shizuoka,” he shares, and “My mother, Setsu, was born in Akita Prefecture.” As a nisei, his mother worried about “a son who can’t speak to his grandma and all of his other Japanese relatives,” so she insisted that he attend Asahi Gakuen in Los Angeles every Saturday. There, he took academic classes with native Japanese students and recalls feeling largely out of place.

“Back then, it wasn’t even in Orange County. We had to drive up to LA,” he shares. “I resented it. I had a little bit of a different pronunciation. I had a first name ‘Joseph’ even though they used my Japanese name. I remember a lot of times kids having bento, and I’d have a sandwich. It was just so hard for me.”

In spite of his protests, Joe’s parents kept him enrolled through his freshman year of high school until the workload split between his regular school and Japanese school was too much to juggle. It wasn’t all bad, he recalls, sharing that he was able to make friends there and, in fact, still keeps in touch with one who lives on the East Coast of the U.S. Still, the experience did very little to endear Japanese language and culture to Joe, who had a difficult time with both learning subject matter and content in Japanese and making friends with other students who “every three or four years would move back to Japan.” He became resentful about “not being able to go to sleepovers and being late to Saturday baseball and basketball practices.” To make matters worse, his Japanese-American friends at the Wintersberg Presbyterian Church, where his father was the Japanese-speaking pastor, didn’t have to attend a Japanese school, so for Joe, the experience did, at times, feel needlessly punishing. His parents, however, held their ground, and confidently told him that he would be thankful one day. It would take many more years for their prediction to come to fruition, but it came nonetheless.

Even as he transitioned from high school to college to working professional, the Japanese language seemed to follow Joe like an opportunity waiting to be grabbed. “I tore my ACL right before my senior year in high school, so I decided I wanted to coach, and I went to my head coach who said I need to become a teacher.” Thinking that a history credential would be the fastest route to his goal, Joe enrolled at California State University Long Beach, only to learn from his counselor that the highest need fields were actually science, math, and foreign languages.

Interviewing exchange students at Western in video class_

“I told her I hated science and math, and she said, ‘Well, do you speak a foreign language?’ I told her I speak Japanese fluently and she said, ‘Well, there you go.’”

It was not what Joe had planned to do, nor what he particularly wanted to do, either. He recalls struggling with “the grammar side” of learning the language formally. To this, he credits Professor Yoko Pusavat for not only holding him to high standards but following through with her strict pedagogical practices. “I was a terrible undergraduate student since I was taking my Japanese classes simply for an easy A. In fact, some of my undergraduate Japanese grades are ‘B’ because I remember her saying I have not learned anything and I am never there, despite having like 99% in the class! Once I got to my upper division courses, the grammar side got even harder. I knew how to speak it just because I spoke it at home, but I wasn’t going to be able to explain dictionary form, masu form, and te form to my students.” Still, Joe graduated with a BA in Liberal Studies: Japanese and became the first Japanese teaching credential candidate at CSULB—huge steps considering he had never imagined himself being a Japanese language teacher at all.

My parents at Dodgers in Toronto to see Shohei Ohtani

“I think I was about twenty-three when I said thanks to my mom and dad. I go, ‘I get it now.’

It finally hit me that I have a skill that a lot of people don’t, and that’s how I got my teaching job.” Even then, Joe recalls that his appreciation was influenced more by having a job than of the language itself, but it was a start—one which he can look back and laugh on now that he understands just how important his journey has been: “Now that I’ve gotten older, I’m close to my cousins in Japan. I talk to them almost daily in Japanese—that kind of stuff I would have never imagined forty years ago.”

In spite of his initial hesitation to become an educator, Joe immediately grew into his role. While assistant coaching for Tom Danley at Katella High School, the superintendent proposed launching a “Pacific Rim Language” program. Within a few days, Joe was writing his own curriculum—no textbook provided by the district—in anticipation of the launch in two weeks. His tenacity was evident in his successful pursuit of this critical task: an infant program needed legs to stand on, and Joe rose to the occasion as its guide. Now, thirty years later, he proudly shares that the district offers “Korean, Vietnamese, and Chinese at multiple schools.”

His personal growth as a teacher ties together many loose ends into a stronger, lasting narrative. Although teaching was initially the only way to reach his coaching goal, Joe’s teaching and coaching philosophies are nothing but responsive and relevant, earnestly investing in each and every student and player. “You truly have rewards that money can’t buy. You’re helping, hopefully, kids and influencing, guiding them. Hopefully by taking the language, it helps to cultivate open-mindedness toward our world that’s becoming more and more global. That’s the part I think is my responsibility as a teacher.” For Joe, this responsibility is not one that can be taken lightly.

Joe with Mayor Takahashi (current mayor of Anaheim Sister City Anaheim)

“What’s hardest for me as an educator and a coach are the ones where I wonder, ‘Could I have communicated better? Could I have done something better?’ Ultimately, as teachers, as educators, as coaches, we make an oath to help kids.”

Joe and Mayor Mori (current mayor of Long Beach Sister City_ Yokkaichi)

And this work is by no means limited to the four walls of the classroom. Joe is an active member of sister city initiatives for both Long Beach-Yokkaichi and Anaheim-Mito. “To see the connections between the students and teachers of both countries and cultures brings a lot of joy to me. It’s a TON of work but worth it when you see how it can impact the kids who are the future.”

The sister city program offers numerous opportunities for students and educators in Long Beach to participate in exchange programs, either hosting Japanese visitors or becoming visitors themselves in Yokkaichi. It is more than just a chance to visit another country, though. These opportunities facilitate significant cultural exchange, encouraging the participants to immerse themselves in the experiences, such as the Yokkaichi English Fellows program, which gives English-speaking educators who have graduated from Long Beach State placements in English immersion programs as assistant language teachers in elementary and middle schools. “One of my language students from Western who graduated from Long Beach is teaching over there,” Joe says, “It can be hard to find people to volunteer their time and resources, so we have quite a bit of turnover, but we have a strong core. Hopefully she’ll be part of our organization long term.” It’s an opportunity to participate in a meaningful cultural exchange, which extends beyond “a cheaper or free trip to Japan” and facilitates authentic reciprocal relationships. Joe shares his own experience as a participant in these exchanges: “We usually host a teacher, and I still talk to the teachers all the time. We exchange ideas and pictures, and it’s been helpful to my Japanese classes at Western High School.”

For Joe, though, nothing about these programs is more important than “the friendships, the students, the communities—getting to know and understand one another.”

There is a necessary person-to-person connection that happens in these exchanges which ultimately makes the experience what it is. He recalls, for example, taking Japanese exchange students to the Japanese American National Museum in Little Tokyo. “They always say that they had no idea, and they have gone back to Japan to share about this.” His own students, as well, experience their own kind of culture shock just from having visitors in their classroom space. “They’ll be like, ‘Oh my gosh, Mr. Aihara, they’re so nice. They’re so polite.’ When they have questions, they ask things like, ‘So what happens if you do use your cellphone?’ and the students from Japan will say, ‘I don’t know because we aren’t allowed to use it.’” These opportunities push students—and their respective adults—to acknowledge, articulate, and accept cultural differences in ways that build empathy and compassion. “I get a lot of satisfaction seeing them connect and have so much fun in spite of their differences.”

Part of this personally vested interest in these opportunities comes as a direct response to Joe’s own muddled relationship with a hyphenated identity from childhood. “I said and did a lot of things to my mom and dad that I am not proud of,” he shares. Although he understands the reason his parents pushed him to Asahi Gakuen every Saturday, the dissonance was a rather extreme hurdle for a child to reckon with. Now, as a facilitator of transnational cultural exchange, Joe says, “I feel a connection, almost an obligation, to connect my parents’ country and my ancestry with the country where I grew up. It’s fun for me because now that I’m fifty-five, I have these two countries—my mother country and my home country.”

Joe’s first time actually visiting Japan was in sixth grade when he met his grandparents and other relatives. “I just remember that being a fun trip and just loving the different culture. I could walk down and buy stuff at the 7-11 as an eleven year old.” But Joe wasn’t one to jump at every opportunity to visit his parents’ country. He recalls finding excuses to stay back in the U.S. instead of traveling abroad. “When I was in high school,” he shares, “my grandpa passed away, and I remember talking my way out of it and using basketball as an excuse. My parents and brother went to my grandpa’s funeral in Numazu, and I was like, ‘I don’t want to go. I’d rather be with my friends.’” It’s a regret that Joe carries with him to this day, but now, with clarity and appreciation on his side, he hopes that his grandpa understands and forgives him. “I just wanted every reason not to go, and now I’m trying to find every reason to go.”

As much as attending Japanese school grated on Joe as a child, he now credits teaching Japanese for his close relationship to his heritage. “I remember I started teaching in ‘95, and I went to Japan for a program through the Japanese Business Association. I vividly remember it was my first year of teaching—I was twenty-five—and we had gone to the Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum as part of our trip.” It was an eye-opening experience for Joe; for the first time, the relationship between Japan and the U.S. started to make sense, and he realized that it’s through conscious effort and communication that this history lives on. He recalls the way the pieces began to fall into place: “I always have this feeling that’s hard to explain. All my relatives live in Japan. They’re from Japan. And I’ve been a U.S. citizen my whole life. That’s the first time I saw my relatives and saw my cousins, and that sort of triggered the whole thing.”

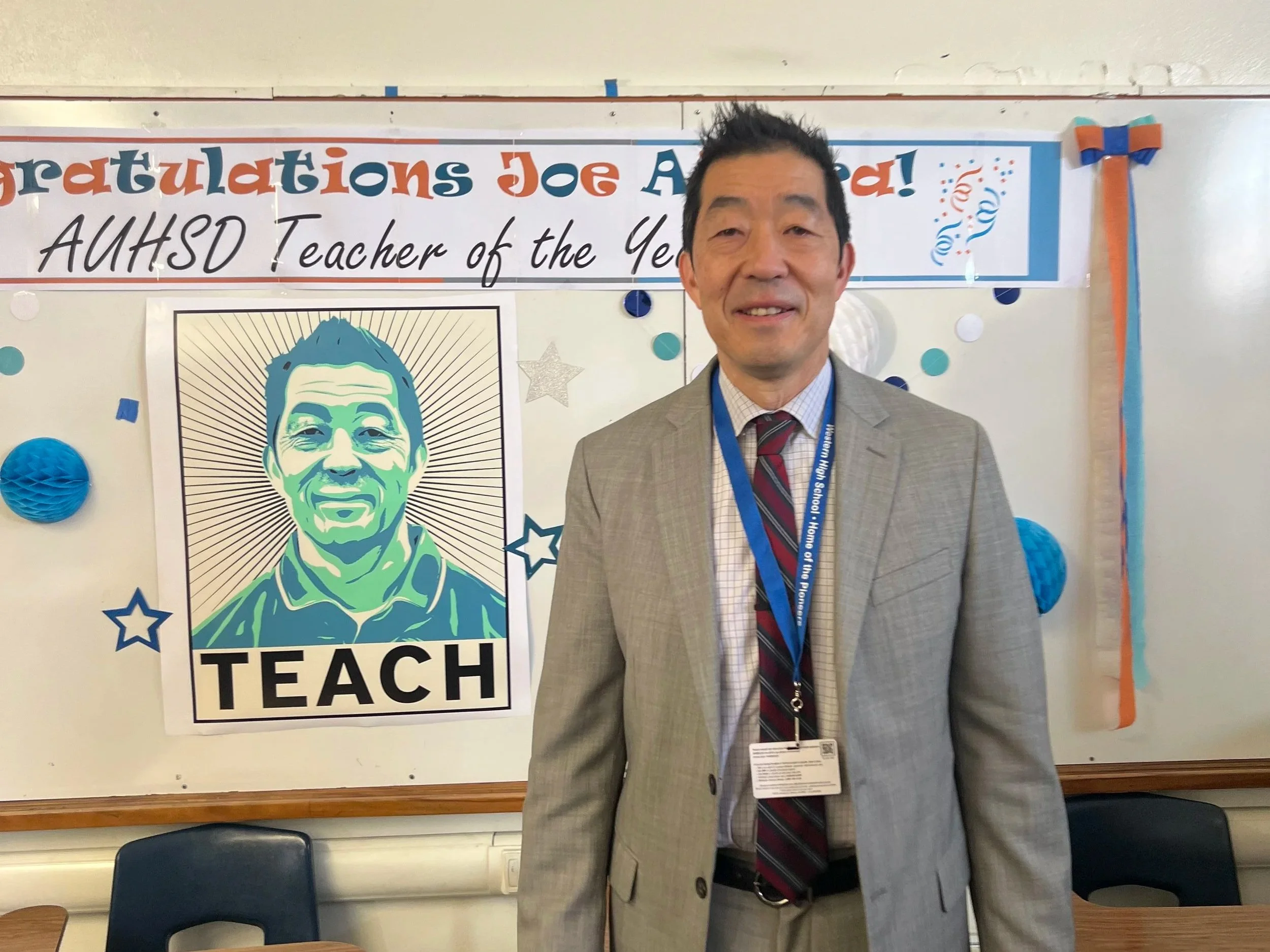

AUHSD Teacher of the Year

From there, the learning was no longer a burden; it was a privilege, a unique opportunity to advance in both professional and personal development at the same time.

“This whole connection with my cultural background didn’t start until I started teaching. I always remember my mom going, ‘One day, you’ll understand.’ And I go, ‘I’ll never understand it.’ But it’s all part of growing up, and I’m grateful now.”

His Japanese classes at Western High School encourage students “to connect and to learn more about the Japanese culture,” rather than just cramming vocabulary and grammar forms for a test.

“Each year, I try to incorporate some of the Japanese traditional culture.” It’s a well-rounded experience, designed to prioritize a lifelong awareness of cultural sensitivity. In addition to walking students through a traditional tea ceremony, Joe even requires students to try natto. “I tell them, ‘You’re going to have an open mind to it. You’re going to try it once, and from there, if you don’t like it, that’s fine.’” Rather than driving students away, it’s an invitation to share their own home cultures with Joe in exchange; the safety of his class is one that encourages students to bring their authentic selves and to develop first and foremost as humans.

Teaching Japanese puts Joe in an interesting position because it isn’t a required class. Although students have a foreign language requirement, everyone who takes Japanese has signed up for it. They all want to be there. “Things have really taken off in the last ten years because so many of the kids are interested in anime and manga and pop culture.”

While it is encouraging to know that students have a genuine interest in learning his class’s subject matter, Joe also feels a grander sense of responsibility to honor their goals precisely because they are so earnest about learning.

He neatly draws a parallel to coaching and the many players who have gone through his program: “With coaching, you have something that they truly want: that’s basketball and playing in the game. I utilize that to hopefully motivate them to become better characters and people and athletes.” It’s this clarity to his mission that brings him the most satisfaction, as both an educator and coach.

Joe recalls in the 1995-1996 season Coach Danley told him, “‘If you’re doing this for a championship, get out because I’ve never won the last game of the season.’” Hearing these words from the winningest coach at the time was bewildering to Joe then. All he wanted was to win. When he was assistant at Marina High School under Steve Popovich, their team made it to the CIF Finals. “I was twenty-one or twenty-two, and I remember him giving me the access lanyard. He goes, ‘Don’t get used to it because this is probably the first and last time.’ I’m looking at him going, ‘I’m going to be back here every few years.’ That was 1990. I actually contacted his son after 2022 when we won CIF, fortunately. I went, ‘Can you please tell your dad that I never imagined it would take 30 something years to get back?’”

After winning CIF in 2022

Now a veteran in his own right, Joe understands that winning, while exhilarating and important for a competitive sports program, is not where his attention is best served. “It’s about the relationships you have with your players. What I’ve learned and gotten way better at is you put good people around you. That’s something I didn’t do when I was younger. I had to be in control of everything.” And that’s perhaps what has kept Joe in the teaching and coaching game for as long as he has been: the compassion, the self-reflection, and, above all else, the willingness to see his own development as still in-progress.

“I wish I would have known all of these things at twenty-five, but you’re also adjusting to the kids of 2025 instead of 1995. It’s a whole different world.

That part’s been challenging for me, but I think I’m evolving there, as well. Times are just different, and I understand that. I don’t want to be stubborn. You’ve gotta adjust and adapt, and that’s what we’re doing.”

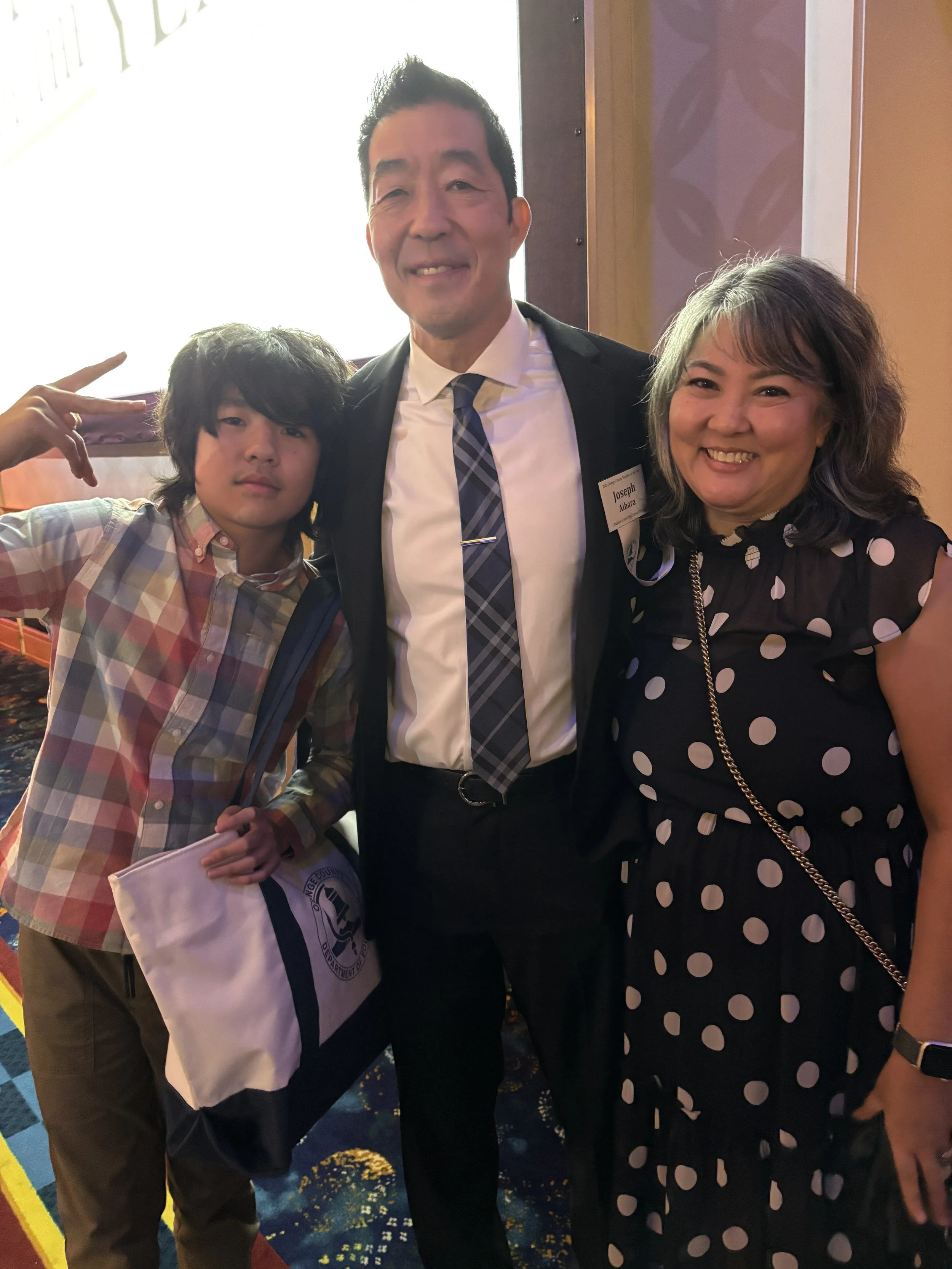

Kristen, Luke, and myself from Y19

One of the things that’s been most eye-opening for Joe across his career is how vast the Japanese-American experience really is. “My wife Kristen Akiko’s (née Miyamoto) side of the family went through internment camps—her uncles and aunts. My father-in-law was born in Poston. I didn’t really know a lot about that side of things because my parents came here in 1968.” This realization has helped Joe with learning how to adapt to fit the times as the Japanese-American experience changes through generations. As the Yonsei 18 and Yonsei 25 coach, Joe got to experience first hand how the youth Japanese-American basketball culture had evolved from his time with WPC.

“I knew that Yonsei wasn’t just about winning basketball games, so I was okay with that. I was older, so I understood that it wasn’t about just basketball; it was using basketball as a tool for learning about culture and experiencing different culture and your heritage.” Although in his experience as a SEYO player, things were “way more social, more fun being with friends” than winning, as well, there was an added layer to the Yonsei experience. “You only have so many practices and then there are dance practices and the fun aspect. I had great experiences with Yonsei that I don’t know if I would have had if I had been a coach at twenty-nine or thirty. But because it was later, Japanese culture was very important for me. There were times with Y25 where I wondered, ‘Is the JA culture having a bit of slippage?’ but I realized that it’s just the generation is different. It was great. Hopefully they make lifelong friends with their host families and when they come back here, they can continue that relationship.”

Luke, Kristen, and Joe at OC awards dinner

As Joe raises his own son, Luke Hiroshi, he reflects back on how the journey that shaped his identity was so unique to him. “I’ve never pushed it with him,” he says of his son, emphasizing that while heritage is important, developing a personal connection, rather than having one forced upon you, is just as critical.

“I wish there was a time machine, and I wish I could go back and say, ‘It’ll all work out.’ Maybe I’ve gotta make up for those teenage and elementary years,” he shares with a laugh.

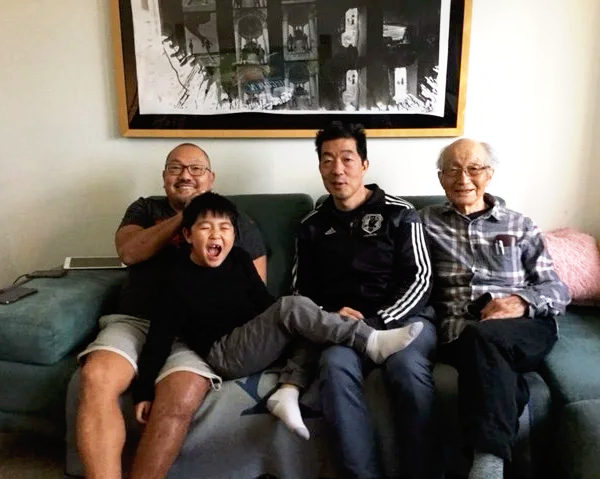

My brother, Luke, and my dad

For Joe, he sees on a daily basis—through teaching, coaching, and volunteering with the sister city programs—that culture and identity are never static; they evolve and grow and take on new forms with each new generation, with a multitude of variants therein. “Now that I’m older, I’m trying to share all the things and get kids to understand these things because they are the future.” This future which Joe hopes to prepare his students for is one of integrity, empathy, and self-acceptance. The work that he does to build toward a compassionate global community pays forward his own struggles to reconcile his heritage and national identities, giving future generations a necessary example of how to not feel stuck between either-or but, rather, how to choose both.