For more information on Hayashi’s art, visit gyotaku.com.

PLAY, PRINT, EAT

By Kristen Nemoto Jay

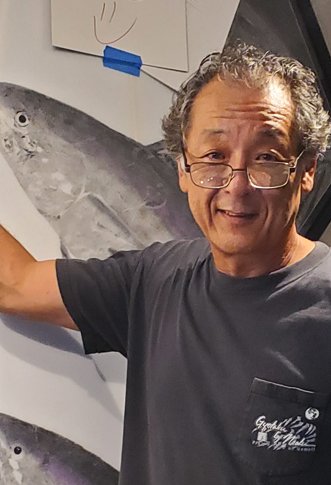

Despite the faint and dusty covered sign hanging above his place of business, Hayashi’s customers have no problem finding him as his popularity turns many customers into repeat clients and lifelong friends.

Step into the shop of gyotaku (Japanese fish printing) artist Naoki Hayashi and you’ll find a vintage Mustang parked within the complex, covered in dust and debris, one of his many do-it-yourself projects that he’s got on the side.

“I like to fix and create things,” said Hayashi, explaining how he once worked for a Mustang shop in Anaheim, California during his college days in the ’70s. He helped restore nine Mustangs and Cougars, one of which was gifted by the shop owner — a 1969 Mustang fastback — and used to drive cross country while taking time off from school for two semesters.

Hayashi’s modest studio is tucked away in a strip mall next to a laundromat and a screen and glass repair shop in Kāne‘ohe, O‘ahu. There, you’ll see various gyotaku on shoji rice paper, stacked waist-high on tables waiting to be brought to life by Hayashi’s brush strokes. From local restaurants and homes to walls within Europe and corporate offices, Hayashi’s prints are everywhere. All by “word-of-mouth” he says, as many have tried but failed to get him to advertise. His reputation has been built by trust and his quality of work.

“My business is the best because I’m my own boss,” Hayashi said. “Thanks to my clients who have been supporting me since day one when I stopped chasing money, when I started focusing on what I can give, that’s when my world turned.”

Born in Kyoto, Japan, Hayashi moved to Hilo, Hawai‘i island to live with his grandparents at age six. Later he attended a boarding school in Kamuela where he met his Algebra teacher and fishing guru Jim Rizzuto, who became Hayashi’s mentor and took him fishing on weekends if his math homework was done. Those trips fed Hayashi’s love for the ocean, along with his fascination for Jacques Cousteau. His grandfather’s friend showed him how to preserve his catch on paper by creating a gyotaku, and that same year he printed his first one: a big eye reef fish known as menpachi. Soon thereafter, friends began asking him to make gyotaku from their recently caught fish and Hayashi began making them as gifts for family and friends.

When he moved to Southern California for college to study biochemistry, he put his art on hold. Keeping to his studies -- what he felt society wanted from him more than himself at the time -- became his priority. But after college, he had a change of heart about his goal of working for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in San Diego and moved home to the islands.

His love of the ocean lured him back and he soon connected with a dive shop owner who needed Hayashi’s bilingual skills. The owner offered him a barter and said if he helped take out the Japanese tourists on the weekends, he would make him an instructor for free. Hanauma Bay became his office for the next 17 years. He was popular with both the Japanese tourists and scuba enthusiasts, while also helping certify city and county officials as lifeguards and firefighters. The ride was great but life once again became about capitalizing on profits –the reason he had turned away from the NOAA to pursue a different path. He foresaw his life as if he’d already lived it, picturing himself owning his own dive shop then hiring instructors to continue to do the work, none of which appealed to him. He wanted to follow his own passions involving his love of the ocean. That brought his gyotaku teachings back into his life once again.

In the mid-1990s, Hayashi launched Gyotaku by Naoki. He figured he was on to something special after Hawai‘i Kai Towne Shopping Center put out an advertisement for an upcoming Christmas art show one winter for artists of all mediums. He then went to “City Mill and bought two peg boards to put his gyotaku pieces up on.” He sold out his pieces before noon that day. That same year Hayashi became a member of the former Pacific Handcrafter’s Guild and “Thomas Square became [his] theater.” Gyotaku, which consists of two characters that translate into “fish” (gyo) and “rubbing” (taku), naturally became a part of Hayashi’s life. The ancient form that started 200 years ago to record fishermen’s catches was being reinvented by Hayashi’s bold style, depicting the sea creatures as how they would have originally been seen in the ocean.

Galleries and writers began showing interest in what he was doing. Nohea Gallery regularly began showing his pieces, then restaurants did likewise -- including his most noted customer, Roy Yamaguchi. For 30 years Hayashi’s loyal clientele has kept him in business and continues to this day. His prints range in price but usually cost anywhere from a few hundred to thousands of dollars. A price however, he says, cannot necessarily be placed on the entirety of a gyotaku for it’s the memory of the experience that’s priceless and will last throughout his customers’ lifetime.

“Say that’s the first catch you’ve ever done in your life,” said Hayashi. “That is a once in a lifetime event that you cannot ever get back again …How many businesses say they can capture that memory, which is priceless? ”

“That’s why I am blessed, because every day I get to enjoy the genuine smile from my clients. Money can’t come close to that.”

Hayashi uses water-based acrylic paint on shoji paper, which is a modern version of rice paper. The paper helps with “consistency” of the print, Hayashi says, as its synthetic material helps with its preservation. His most unique prints to help preserve and document its catch are for NOAA workers who find specimens that they don’t even have names for yet. Though final paint touch ups and framing may take some time, the initial gyotaku is done “as soon as possible” as Hayashi wants to ensure he gets the catches back to his clients in time to eat. That’s Hayashi’s general rule for all of his gyotaku creations: He’ll print anything, as long as it will be consumed and not wasted.

“Some people search for ulua their whole life and when they finally catch it, they worry about ciguatera so they don’t eat it and then they throw it away,” said Hayashi. “I get turned off from people who bring [fish] in without having intentions of eating it. I see the health of the world more and I look at what we’re teaching our kids as the future. We need to set a good example for them. I try to make an influence in my art as a vehicle.”

Though the pandemic caused many businesses to close their doors, Hayashi kept his wide open as people were “still waiting in their cars” ready for him to quickly print their catch. Hayashi credits the pandemic as a time when “the universe [was] pushing and pulling in both directions,” which brought on “so much bad” but at the same time “so much good” for him and many others that he knew. Former clients would call Hayashi to see if he still had a past print that he made of their fish, which helped bring back a memory prior to the pandemic.

Along with his printing business, Hayashi visits schools to conduct gyotaku demonstrations and share his love for the ocean and the importance of pursuing one’s dreams.

It’s important to him to relay some of his life lessons he’s learned to the younger generations, in hopes to help them find their own path in life -- even if it’s not the path that others may want for them.

“School is important but it’s not 100% everything,” said Hayashi. “Imagine what this world would be like if we help build on the values of our kids and make them feel good about their individual and unique traits rather than instill in them that they need to always get good grades? Let them experience the joy of what it is to be human. Feel the water, feel the wind and then put the thinking aside and feel like biological beings walking on two feet.”

Today, Hayashi is grateful to have found his “place in this world.” Rather than “chasing money” and what society declares to be “success,” Hayashi finds peace in knowing he’s on his path of happiness, especially because of the joy that he helps share through his gyotaku.